What we’re doing: Community response

In 2006, Juneau’s Mayor asked UAS to prepare a report on the potential impacts of climate change. At the time, the report, titled “Climate Change: Predicted Impacts on Juneau” (the precursor to this report), was one of the few scientific reports on climate change prepared for a local community. The report presented an objective look ahead at what global warming will mean for Juneau. Subsequently, several climate change-related reports and activities were undertaken by the CBJ, including a greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions inventory and reduction strategies, climate change implementation plans, and other projects, many of which are highlighted below and included in the timeline in Figure 20.

After the 2006 report was released, several new local nonprofit organizations were formed to raise awareness and education through public forums and programs to reduce GHGs. A list of these organizations and their contact information is attached in the Appendix.

E. Upgrading infrastructure and mitigation

Effectively responding to climate change can be a difficult task. However, as Juneau’s citizens experience more frequent episodes of flooding, landslides, glacial retreat, and more extreme weather events, public support for investing in climate mitigation and adaptation is growing. While the demand on public funding to fix aging infrastructure is already daunting and heading off future damage from climate change may have not that long ago seemed distant and abstract, rapidly changing conditions have strengthened citizen and government resolve to respond proactively to climate-related challenges.

Juneau’s storm drain system is not built to withstand extreme events

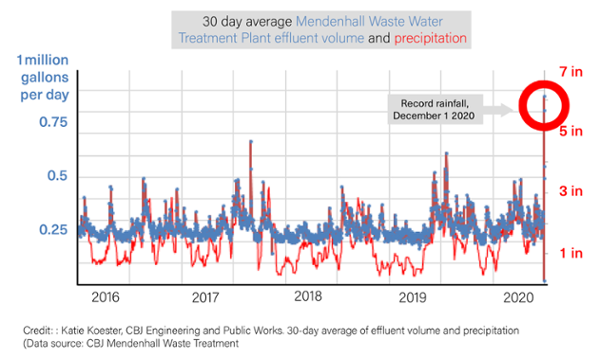

One example of the impact of climate change is the stress being placed on Juneau’s storm drain system. High precipitation events like the storms of October 2019 and December 2020 have overwhelmed Juneau’s infrastructure. Both of these events represent 100-year storms, while Juneau’s storm drain system is designed to handle a 20-year event. More concentrated rainfall results in storm drains overflowing and water backing up into drainage systems, homes, businesses, and streets. The December 2020 storm brought the most rainfall ever recorded at the Juneau International Airport—just shy of five inches in one 24-hour period.1 This storm also created many small local landslides that devastated homes and caused damage to roads and other public infrastructure. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) damage report for the City and Borough of Juneau, the CBJ experienced $4.7 million in damage.2 The Mendenhall Wastewater Treatment Plant experienced a dramatic influx of effluent, partially as a result of residential and business roof drains being illegally connected to the sewer system. Large volumes of fresh water going into the wastewater influent disrupt the ecology of biological treatment and require additional resources to be moved through the system to help it recover.

Many of the issues with drainage from the December 2020 storm involved debris clogging drains, which larger culverts would not necessarily have fixed. Additional engineering and analyses need to go into any recommendations for mitigating the effects of increasing precipitation in the borough.

Figure 15. 30 Day Average of Effluent Volume and Precipitation

The average precipitation compared to effluent intake at the Mendenhall Wastewater Treatment Plant. The outlier corresponds to record rainfall on December 1, 2020. Source: CBJ Mendenhall Waste Treatment.

Mitigating climate change in Juneau

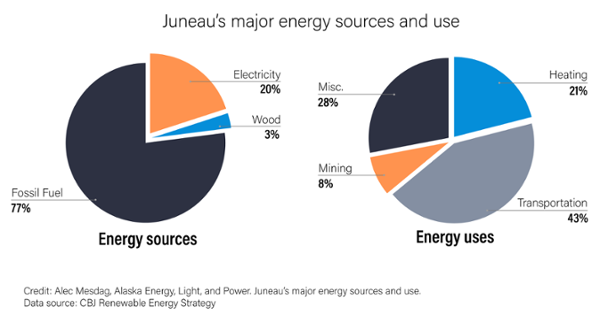

With the 2011 CBJ Climate Action and Implementation Plan, Juneau began planning to measurably reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Actions included encouraging weatherization programs, updating the building code, encouraging all levels of government to reduce emissions in their operations, and extensive public outreach and education, including partnering with the University of Alaska Southeast to develop local professional expertise.3 In 2018, the CBJ adopted the Juneau Renewable Energy Strategy, or JRES, which established an ambitious goal of having 80% of Juneau’s energy provided by renewable resources by 2045.4 While these mitigation actions will help slow climate change in the future, the community is facing the impacts of changes in weather patterns and severe storm events today. Potential mitigation or adaptation measures could include upscaling infrastructure such as stormwater drains to handle more flow, building retaining walls to protect against mass wasting from avalanches and mudslides, and strengthening coastal infrastructure and riparian development.

Adapting to landslide and avalanche hazards

In 2021, CBJ contracted for a hazard assessment and assessment maps for landslides and avalanches in the downtown Juneau area, including Mt. Juneau and Mt. Roberts. The study will be used to inform potential updates to the existing hazard maps created for downtown in the 1970s and adopted in 1987. Key parts of the hazard assessment include an update of surficial geology mapping, changes in slope features and mass movement activity, location of landslide and avalanche types, categorization and refinement of hazard designation map polygons, and preparation of geohazard designation mapping in support of the future development of appropriate zoning, building regulation, and mitigation options.5

F. Upgrading utilities and other energy consumers

Changing winter supply and demand from hydroelectric plants could help meet heating needs

Juneau currently receives nearly all its electricity from hydroelectric plants that have storage reservoirs, including existing alpine lakes and a reservoir behind the Salmon Creek dam. Inflows into these reservoirs do not align with seasonal demand for electricity, as freezing temperatures in the watersheds that supply storage reservoirs reduce inflows for much of the year. In an average year, reservoirs receive only around one-quarter of annual inflows from November to May, when nearly two-thirds of annual electricity is consumed. Predicted increases in average temperatures and precipitation will lessen this effect – more inflows will occur in the November to May period, while the demand for heat in those months is expected to decline with higher average temperatures – and this will in turn allow the electric system to more easily meet heating loads.

Heating loads put additional strain on energy reservoirs and infrastructure

The two primary energy loads to be electrified in Juneau are for transportation and heating, which have differing effects on the grid. The use of transportation fuel in Juneau peaks during the tourism season (see Section C) and integral energy storage allows electric vehicles to draw energy from the electric grid at various times throughout the day. In contrast, the community’s demand for heat increases as temperatures decline, when inflows into storage reservoirs slow, and heating systems do not typically include or require significant heat storage. The lack of storage in electric heating systems means most electric heat is supplied as needed, which leads to overlapping demand for heat and high peak non-heating loads on the grid. Because of these differences, electrified transportation tends to place less strain than heating loads on both the need for reservoir storage and the infrastructure required to deliver electricity to customers

Greater efficiency and reduced energy consumption are needed to balance the costs and challenges of electrification

Accommodating the desire to electrify transportation and heating loads in Juneau will require a concerted effort to manage how electrification occurs to avoid negatively impacting Alaska Electric Light & Power’s ability to meet Juneau’s demand for electricity with affordable, reliable, and renewable sources. The community should pursue complementary efforts to increase the use of electrified transportation, improve the thermal efficiency of buildings, and replace electric resistance heat (such as electric baseboard heaters) with heat pumps. Eventually, the ability to cost-effectively improve efficiency will no longer keep up with increased demand for electricity because of increasing electrification. Conserving energy and using more efficient technology early will ensure the system is not overbuilt and more costly than necessary.

Figure 16: Juneau's Major Energy Sources and use

G. Growing demand for hydropower

With its recent growth in electric vehicles and air source heat pumps, as well as potential increases in centralized renewable space heating and cruise ship shore power, Juneau’s demand for hydropower for electricity is increasing. This section will briefly discuss the current situation with hydroelectric power in Juneau, seasonality and hydropower, planning and development, and potential opportunities for continuing to provide a workable, equitable system that provides predictable, low-cost energy to Juneau and our neighbors.

Current hydropower situation

Juneau is fortunate to have substantial developed and undeveloped hydropower resources, a growing public desire to change to this cleaner energy source, and the natural resources to do that. Hydropower generation in Juneau provides a zero-carbon source of electricity as it does not contribute to atmospheric pollution, including greenhouse gases.1 Hydropower is a readily available local climatic solution for displacing diesel generation for uses that have expanding needs or are not already on hydropower. Transforming Juneau’s energy use toward renewable energy supplies may create regional opportunities to develop and transmit electricity to serve not only increased local but also regional electric demands. Juneau strongly supports increased hydropower to meet needs and climate impact changes, as reflected in the CBJ’s Resolutions 2593 (Juneau Climate Action and Implementation Plan) and 2802 (Juneau Renewable Energy Strategy).

Juneau is positioned to meet hydropower demand as fossil fuel-based heating systems are converted to heat pumps. According to the 2017 Juneau Renewable Energy Strategy (JRES), nearly 70% of Juneau’s homes are still heated by fossil fuels.2 These fossil fuel-based heating systems provide a large potential market for heat pump conversion and a corresponding rise in hydropower demand as economic and climate change decisions are made to convert from local diesel use to more electricity for heating. District energy development identified in the Juneau Climate Action and Implementation Plan (JCAIP 2011) and the 2018 JRES will eventually provide additional growth of beneficial electrification and hydropower development. Further, the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) model identified a substantive increase in electrical power across the United States, providing additional evidence that electrical energy growth is coming.3

Figure 17: US Electricity Share of Energy

Electricity share of final energy doubles from 2016 to 2050 under the High scenario. Source: Adapted from Mai, T. (2018)

Widespread adoption of end-use electric technology would result in substantial fuel, electricity, and total energy consumption shifts. Beneficial electrification, which is the substitution of fossil fuel use for cleaner and, in many cases, lower-cost, electricity, may environmentally and economically fuel a continued market shift toward displacing fossil fuels in Juneau and elsewhere.4 This substitution could provide the opportunity and impetus for hydropower growth to meet local and regional beneficial electrification needs.

Increasing temperatures will alter seasonal runoff patterns

It is well established in this report that climate change is upon us, and that Juneau can expect warmer temperatures and more precipitation. The seasonality of precipitation causes variability in hydroelectric generation. Geographic regions with distinct seasonal rain cycles and snowmelt typically experience fluctuations in generation due to precipitation’s influence on flow.5, 6 The U.S. Dept. of Energy (DOE) recently reported to Congress about the effects of climate change on federal hydropower, with in-depth analysis of the percentage change in the projected multi-model median temperature, precipitation, runoff, and hydroelectricity generation in each Power Marketing Authority (PMA) study area in the United States from ten-downscaled climate models. Overall, air temperature is projected to increase in all PMA areas annually and seasonally for both the near-term (2011-2030) and midterm (2031-2050). While the increase in temperature may not directly influence annual runoff, it will cause earlier snowmelt and a shifted seasonal pattern in runoff.7

Predictions of climate change impacts on Southeast Alaska hydropower made in 2010 appear to be validated by subsequent regional research findings.8, 9 As noted in 2010, climate variability and change both have implications for shifts in the timing and magnitude of river discharge that could pose challenges to the management of capacity-limited reservoir systems.

Potential planning and development for resilience toward drought and runoff variability

Climate change impacts pose challenges for hydropower planning and development. The recent Southeast Alaska drought, beginning in 2017 and culminating in 2020, is a reminder.10,11 The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that more frequent droughts and changing rainfall patterns may adversely affect hydroelectricity generation in Alaska as well as in the Northwest and Southwest regions of the United States.12 Further, the GAO provided recommendations to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and DOE to develop strategies to enhance grid resilience and identify and assess climate change risks to grids.13 A well-planned transmission grid provides more flexibility by enabling more generation resources to be built in the lowest-cost locations.14 An integrated grid system, like that in climatically similar Norway, makes it possible to take advantage of spatial variability in precipitation and runoff. Grid resilience options include consideration and integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), which are becoming more common in Alaska and elsewhere.15

Climate change impacts that threaten the local energy supply might be mitigated with regional grid leadership and planning to help Southeast Alaska reduce environmental and climate change impacts by building and transmitting lower-cost hydroelectricity to current diesel-using communities. This could possibly not only reinforce climate resiliency but also help provide economic and environmental justice.16 As mentioned above, when hydroelectric capacity grows in Southeast Alaska and the system becomes more interconnected along a physical grid, the region could have more options for managing climate risk.7 Moving lower-cost hydropower to displace fossil fuels in higher-cost diesel communities, cruise ship dock electrification, and mining loads reduces regional GHG emissions and enables additional community tools to deal with climate change.

Opportunities to mitigate and adapt to climate change through electrification

Juneau is turning toward clean, less expensive electricity from hydropower, and demand will increase. There are major decisions requisite to building more infrastructure for hydropower, but the need and desire are there- from EVs to heat-source air pumps, to cruise ship dock electrification, to partnering with Juneau’s neighboring communities and industries. Feasibility studies and funding efforts for an interconnected power grid including the integration of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), need to continue as well as hydrological modeling and integrated resource planning as Juneau responds to climate change. These areas of expansion, research and planning provide potential opportunities for Juneau to further integrate hydropower into the CBJ’s energy future.

Interconnected power grid

An increasingly interconnected power grid in Southeast Alaska might minimize climate impacts. As hydroelectric capacity increases and the system grows increasingly interconnected along a physical grid, the region may have more options for managing climate risk. Grid optimization and incorporation of BESS help stabilize grids, but also increase reliability against outages.

Continued hydrological modeling

Planning and development will require adaptation to new conditions in hydrological modeling to capture and reflect the anticipated and continued changes in seasonal precipitation caused by long-term climate change.

Integrated resource planning

IRP is a planning methodology that integrates supply and demand-side options for providing energy services at a cost that appropriately balances the interests of all stakeholders.17 Incorporating JCAIP and JRES into a Juneau IRP would integrate climate change and beneficial electrification into Juneau’s energy planning future. Alaska does not currently place IRP requirements on utilities, but it is common in other states.

H. Leading a shift in transportation

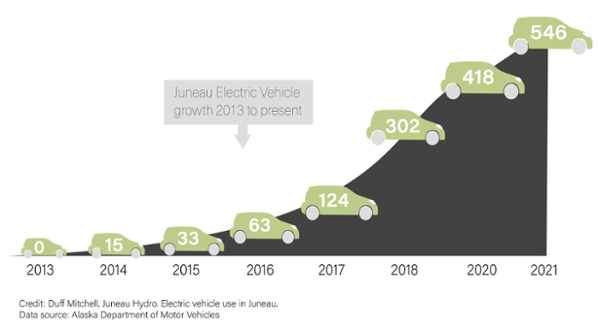

Juneau is a leader in US electric transportation

The rapid transition from internal combustion engines (ICE) to zero-carbon electric transportation represents an unprecedented adoption shift that is swiftly occurring worldwide and one in which Juneau has taken a US leadership role. Juneau already boasts one of America’s heaviest per capita percentages of electric vehicle ownership. In 2021, Juneau’s Capital Transit purchased the first electric bus for Juneau’s public transportation system. Capital Transit has secured federal funding for several additional electrical buses that will provide quieter and cleaner transportation, lowering operating and maintenance costs and greenhouse gas emissions.

Electric alternatives for delivery trucks, construction equipment, and marine transportation represent a competitive market opportunity

Most local electrical transportation has focused on vehicles and buses, but the larger market development involves delivery trucks, mining equipment, heavy construction equipment, and marine transportation. In Alaska, 47% of the vehicles on the road are CUVs/SUVs, while 30% are pick-up trucks.1 Few electric vehicles are sold in these market categories, but recognizably represent a large market for near-term Juneau EV adoption as more electric SUVs and pick-up truck models enter the market. Delivery trucks, heavy construction equipment, and marine transportation are also migrating to electric, with new model entries competing on life cycle and operation cost and displacing fossil fuel models.2, 3, 4

Marine electric transportation could mitigate climate impacts and bring cost savings

Interestingly, the conversion of Washington State’s largest ferries to electric has already begun with the State of Washington VW Settlement funds.5, 6 Similarly, BC Ferries (the British Columbia provincial ferry system) is operating an electric ferry fleet with planned expansions.7, 8 BC Ferries has announced its intent to build seven additional battery-electric hybrid Island Class ferries in British Columbia.9, 10 The implications of marine electric transportation for Juneau and Southeast Alaska include not only mitigation of climate change causes like greenhouse gases and effects like ocean acidification, but it could bring cost savings to the Alaska Marine Highway System comparable to those currently enjoyed by the Washington and B.C. ferry systems.

Figure 18: Electric Vehicle Use in Juneau

Juneau has one of the highest per capita percentages of electric vehicle ownership, with growth since 2013. Development of electric alternatives for SUVs and pick-up trucks could present a large market for local EV adoption.

Electric ferry docking infrastructure

Dock electrification should be viewed as charging stations for current and future hybrid vessels and not just used for ship hoteling needs while in port. Juneau was the first port in the world to provide visiting cruise ship industry with electricity, and the community is exploring expansion to CBJ’s publicly owned docks.11 Future Juneau and regional dock electrification may encourage and enable diesel hybrid battery systems where vessels could use shore power to charge batteries in Juneau, similar to what the Hurtigruten cruise line and the electric ferries in the Washington State and BC Ferry systems do at other ports.12, 13 BC Ferries announced in September 2021 that it will convert one-half of its 36 operating ferries to electric.7,14

I. Maintaining mental health through community and recreation

Climate change impacts our mental health, with some more affected than others

The World Health Organization maintains that climate change is one of the greatest threats to global health in the 21st century.1 While the physical drivers of climate change will impact environmental determinants of health— clean air and water, as well as food and energy security—even the awareness of anthropogenic climate change can impact mental health. Acute weather events (such as the landslides that impacted Haines in December of 2020, or more extreme Taku winds) create immediate anxiety, but more gradual changes in our environment (the recession of the Mendenhall Glacier, for example), as well as the long-term existential threat of climate change also impact mental health in ways society is just beginning to understand.1

These impacts are not evenly or equitably distributed. As the climate justice movement reminds us, climate change will disproportionately affect the economically and socially disadvantaged. Moreover, climate anxiety can exacerbate existing mental health issues, as well as broader socio-economic stresses; for example, we should be asking how climate change stress may compound transgenerational trauma associated with colonization.

Time in nature and access to outdoor spaces can help mitigate mental health challenges

While we monitor the mental health impacts as a community, we can also mitigate them. We know that spending time in nature can reduce stress, anxiety, depression, and the feelings of loss that often accompany change.2,3 Parks, trails, and recreation areas take on even more importance by providing opportunities for people to connect to the greater world around them and come together with others in the community, all leading to greater individual and community resilience and increased capacity to cope with and adapt to the changes and challenges that we are facing.

Careful planning is needed to manage the use of and impacts on recreational spaces

An increase in demand for recreational spaces has led at times to conflicts between user groups, particularly motorized vs non-motorized vehicle users on trails and vessels vs marine mammals. This is especially true for winter recreational opportunities, such as cross-country skiing at Montana Creek and in the backcountry adjacent to Eaglecrest Ski Area. Climate change needs to be carefully considered as the CBJ plans, manages, and mitigates climate impacts on recreational areas, including those along the waterfront, in low lying areas, and at the developed ski area at Eaglecrest, and the opportunities these places provide.

J. Food security

Wild foods and food history

Before colonization, Indigenous peoples living in the Juneau area subsisted solely on the area’s abundance of wild food. Some of the more important subsistence foods threatened by climate change are highlighted in Tlingit Haida’s Climate Adaptation Plan, which includes a ranked list of specific foods and resources organized into three Key Areas of Concern. These rankings were developed using a vulnerability assessment consisting of climate impact variables, environmental stressors, and relative importance to communities. The three levels of importance are labeled Very High Priority, High Priority, and Medium Priority. For any culture with a non-hierarchical view of the natural world, this kind of value ranking is counter-intuitive; the fact that CCTHITA found it necessary to rank the foods that physically and spiritually nourish its members demonstrates the degree to which climate change is already affecting traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering activities.

Key areas of concern for local Tribes

CCTHITA’s Key Areas of Concern form the basis for implementation strategies. As next steps, several actions are listed for each key area with qualitative information, including cost, ease of implementation, political/community support, timing of action, and partnerships. The fact that traditional wild food sources are now being ranked so that Indigenous people can better manage harvests under the limits imposed by climate change is a testament to the resilience of the Tlingit and Haida people. Faced with the bitter facts of change, the authors of the Climate Adaption Plan opted to tackle the situation head-on and find ways to adapt. The broader community can learn from this, as everyone in the CBJ can expect to have to adjust to changes in their food supply brought on by climate-related factors.

Juneau’s cultivated food history

At the turn of the century, after Juneau was settled as a gold mining town, there were few local non-wild cultivated food sources. With the exception of a few vegetables that families grew, and a small dairy production, food was imported from out of state. Beginning in the 1890s, several dairy farms started up in Juneau. However, with the advent of air service beginning in the 1940s, and improved refrigeration, the dairy farms were no longer profitable, and by 1965 the last dairy had closed.1

Climate impacts and supply chain problems highlight the importance of greater food independence

Economic globalization, including advances in transportation, have dramatically changed the lifestyle of people in the CBJ and throughout Alaska. Juneau currently obtains as much as 95 percent of its food supply from out of state.2 This is alarming, given the current stressors on food production outside of our state from climate change, COVID-19, and supply chain problems. We are starting to recognize and deal with the precarious situation we are in. We need to move toward greater food independence. Time is important for food quality--vitamins C, B, and E are all important antioxidants that are sensitive to time—spinach stored at room temperature loses between 50 and 90 percent of its vitamin C within 24 hours of being picked.3 Yet most of our food arrives after spending at least four days on a barge from Seattle. The benefits of having an abundant and affordable locally grown food supply cannot be overemphasized. Climate change provides an opportunity and motivation to support greater local food production using new technologies, taking advantage of an extended growing season and Juneau’s market for quality food.

K. Large cruise ship air emissions

Cruise ship port calls and passengers are projected to increase

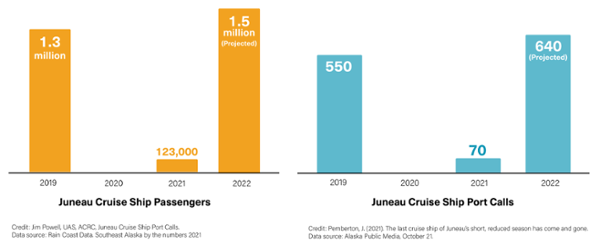

Visitors have been coming to Juneau on cruise ships since the late 1880s to enjoy the dramatic scenery, rich cultures, and wildlife of Southeast Alaska. Today, Juneau is a major global cruise ship destination with up to six large cruise ships docked or at anchor in the harbor at any one time from April to October. Carrying thousands of passengers each, the number of cruise ships visiting Juneau each year has significantly increased. In 2019, there were a record 549 port visits by large cruise ships carrying approximately 1.3 million passengers. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic stopped all port calls, with cruise traffic only rebounding slightly with 70 port calls in 2021. 1, 2 Projections for the 2022 cruise ship season are 639 port calls, far surpassing the record 2019 season.

Figure 19. Juneau Cruise Ship Visitors

The number of large cruise ship port calls in the Juneau harbor in 2022 is anticipated to be 639, far surpassing the record-breaking 2019 season.

Cruise ships are a major air pollution source

Ship emissions constitute a large, and historically poorly regulated, source of air pollution. 3 Large cruise ships burn bunker fuel oil, marine diesel oil, and marine gas oil that release substantial amounts of CO2 and hydrocarbons, both well-known greenhouse gases, into the atmosphere. 4, 5 While in port, large cruise ships burn approximately 320 gallons of diesel fuel per hour—the equivalent of 21,000 diesel-powered trucks. 5 Early in the 2019 cruise season, cruise line companies worked with the state of Alaska to lower their emissions by reducing idle times in the harbor and switching to a low sulfur marine fuel while in port. 6 It is difficult to compare Juneau’s 2019 cruise ship-related air quality impacts to previous years’ as no monitoring data exists for 2018, but city officials received fewer complaints in 2019 than in the previous two years. The data collected did not identify a single maximum impact site but indicated that various parts of downtown Juneau were impacted simultaneously by emission plumes, the severity of which depended on weather conditions. 6

Available studies show that cruising is a carbon-intensive activity; in fact, cruising has been demonstrated to be a more carbon-intensive mode of international transport than aviation. 7 Major cruise companies score low on air pollution, with all but one of the 18 companies reviewed in the Cruise Ship Report Card receiving a score of “C” or lower. 8

Low carbon, renewable shore power will reduce emissions and improve air quality

Juneau and the state of Alaska have taken steps toward mitigating air emissions from cruise ships. The CBJ, in collaboration with Princess Cruises, led the world in 2001 as the first locality to offer land-based low carbon, renewable energy (hydropower) as a technological alternative to letting ships’ engines run in port. Currently, more than 10 ports globally now have shore power. The CBJ’s 2019 Visitor Industry Working Group has recommended expanding shore power to all ships, and feasibility studies are currently underway. This will greatly decrease greenhouse gas emissions while ships are in port and improve local air quality. The Working Group also recommended that regulations be established to strengthen its authority over the cruise ship industry, which has largely been managed by non-regulatory agreements such as the Tourism Best Management Practices.

International and state authorities have a significant responsibility and opportunity to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Consistent with the 2015 UN Paris Agreement, in 2018 the UN International Marine Organization (IMO), the regulatory body that sets standards and regulates shipping, required ships to reduce the total annual GHG emissions by at least 40% by 2030 and 70% by 2050 compared to 2008. Additionally, the UN North America Sulfur Emissions Control Area limits sulfur to 0.1%. 9 Despite these limits and a 0.50% limit on sulfur in ship fuel oil required globally in 2020 under the MARPOL Convention, to date there has been no systematic monitoring of ship discharges by public authorities, and fuel quality is very rarely monitored. 9

L. Tourists’ views on climate change mitigation

Tourists are willing to pay to decrease their ships’ carbon footprint Cruise ship tourism is largely managed through a combination of industry best management practices, regulatory agency permits and operations, and services. CBJ Resolution 2170, adopted in 2002, outlines tourism industry-related policies and is the government’s guiding document. Voluntary compliance is the main tool for managing tourism in the CBJ, along with some federal, state, or local laws. A recent survey of tourists found that over 71% of adult American visitors would pay more for a vacation in order to decrease their carbon footprint. 1 This equates to more than 182 million people. Even more impressive, 33.20% of people stated they would be willing to pay up to $250 extra to lower their vacation’s carbon footprint and fight climate change. This study suggests the cruise ship industry can move decisively toward deep decarbonization with strong support from its passenger base. Some of the proceeds from the passenger fee for cruise ship visitors collected by CBJ and the state could be used to monitor cruise ship GHG emissions while ships are in port.

M. Lowering greenhouse gas emissions

Local government authorities have a key role to play in responding to climate change, as they control vital areas and assets that affect GHG emissions, such as land-use planning, building codes and standards, transportation, energy infrastructure, waste services, and water and wastewater utilities. 1, 2, 3

Cities are high consumers of energy and producers of waste and GHG emissions. An estimated 30-40% of human-caused GHG emissions emanate from within cities. 4 Over 50% of the world’s population now lives in cities, and that amount is estimated to grow to 60% by 2030. Cities consume more than two-thirds of the world’s energy and account for 75% of global GHG emissions. 5 Given their impact, communities should be leading the way to find innovative solutions to address climate change impacts—particularly in light of our polarized national government and lack of international agreement on specific and enforceable climate reduction strategies. Juneau is an active and engaged community with 19 citizen boards and commissions playing a role in local government. In 2007, the CBJ took the first step to address climate change with a scientific report titled “Predicted Impacts on Juneau,” the precursor to this report. Since that time, the CBJ has issued Assembly Resolutions and policy statements, including an emission inventory, a climate change plan, and energy reduction programs. The most recent policy is contained in the 2018 Renewable Energy Strategy which calls for 80% of Juneau’s energy to come from renewable sources by 2045.

Although the CBJ has produced climate change studies, policies, plans, and implementation strategies, it faces many challenges, including limited resources to make the transition to renewable energy and to adapt to climate change impacts. Most recently, the economic and health impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic and state revenue reductions have stalled much of the momentum toward implementation of the borough’s climate change mitigation program. If resources and funding can be found for supporting private and public projects such as district heat for the downtown core, expanded shore power for large cruise ships, expansion of electric vehicle charging and residential and commercial air source heat pumps, and innovative programs like carbon offset, Juneau can contribute its part to lower GHG and reduce the impact of climate change.

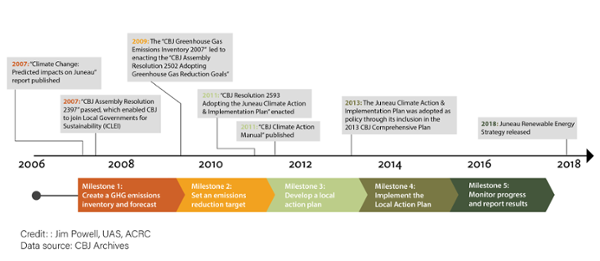

Figure 20. Timeline of CBJ Climate Change Policies and Actions

CBJ’s major policies and actions timeline with the five milestones the CBJ adapted from the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI).

N. Residents taking action

Local nonprofit organizations and partnerships are taking action to adapt to and reduce the impact of climate change

Several local nonprofit organizations have emerged during the past decade to actively fight climate change and increase access to Juneau’s abundant clean, fish-friendly hydroelectric power. These nonprofits contribute to community awareness, raise funds through innovative means, and advocate for local and state climate change policy.

Education and awareness

- Organize free climate and energy education forums with expert speakers and performers

- Organize climate change rallies at the steps of the Capitol and other locations in town

- Promote clean and efficient heat pumps as an alternative to fossil fuel heating in homes and businesses

Funding and resources

- Established the Juneau Carbon Offset Fund, a carbon impact solution that directs offset purchases, grants, and donations to the replacement of fossil fuel heating systems with air source heat pumps in qualified lower-income homes

- Created Juneau’s first clean energy financing program by establishing a low-interest heat pump loan

- Partnered with private enterprise and the CBJ to install a system of free electric vehicle charging stations across the borough

Policy

- Advocated, educated, and worked with local decision makers and residents associated with the CBJ’s Juneau Renewable Energy Strategy

- Launched Alaska’s first Thermalize Campaign, an innovative program designed to accelerate adoption of air source heat pumps through a neighborhood, bulk purchasing, and streamlined process

- Advocate for the state’s Permanent Fund board of directors to divest its investments in fossil fuel holdings

- Advocate for divesting the State of Alaska’s retirement program funds from fossil fuel holdings

- Raise awareness of health and climate issues underpinning the urgency of electrifying Juneau’s cruise ship docks to prevent large cruise ships engines from idling while in port

- Advocate for the electrification of both residential and municipal vehicle fleets, including the Capital Transit bus system

- Advocate for vulnerable people and communities most heavily impacted by climate change.